Senators ask Olmsted for new design of U.S. Capitol grounds, the state of New York reviews a new Albany Capitol building design, and Buffalo and Boston parks seek advice and plans. FLO campaigns to save Niagara Falls scenery, and gains a lifelong landscape office assistant and partner: his stepson and new Yale graduate, John Charles Olmsted, the son of FLO’s beloved deceased brother John Hull Olmsted.

___________________________

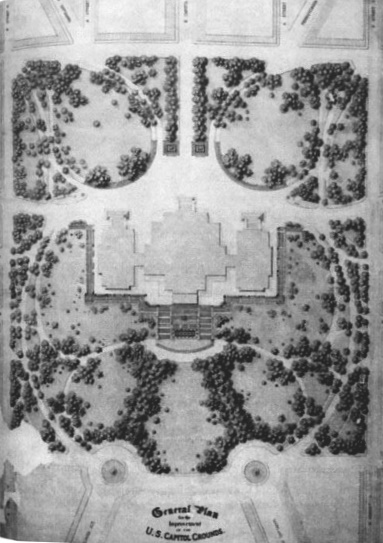

Although they worked together on single assignments years later, by the early 1870s—after almost 20 years of collaboration—Frederick Law Olmsted and architect Calvert Vaux agreed to disband their professional partnership. While Vaux worked alone or with architect colleagues on buildings alongside Central Park—the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Natural History Museum—Olmsted almost immediately received a request from a U.S. Senate committee to begin collaboration on the U.S. Capitol building and surrounding grounds in Washington, D.C.

By 1870, Senator Justin Smith Morrill (1810-1898), the Vermont legislator who introduced the successful U.S. Land Grant College Act of 1862, was a leading member of the Senate Committee on Buildings and Grounds, and held that position from 1870 until 1898. For the next 20 years, he worked with Olmsted to present a grander west front facade and a park design worthy of its hillside site overlooking the Mall and river beyond.

Senator Morrill’s interest in the Capitol grounds, which he had declared as “little better than a common cattle yard,” his longevity on the influential committee, and his own farming operations back in Vermont, made him a natural follower of Olmsted’s landscape ideals. In fact, Morrill was Olmsted’s greatest supporter during the decades of Capitol grounds improvements.

Writing to Senator Morrill and the committee on January 22, 1874, after a visit to the site, Olmsted noted that the old Capitol building and its hilltop locale were inadequate. “Looking from the West…the face of the hillside is broken by two formal terraces which are relatively thin and weak, by no means sustaining in forms the proportions the grandeur of the superimposed mass.” The “weak” earthen terraces now surrounding the new Senate and House additions should be set off, he suggested, with marble staircases and terraces to anchor the hillside and the setting from the western (Mall and Potomac) view.

Olmsted’s previous European trips now came in handy as he offered advice on grand building design. Influenced by old English estates and French palaces, he cited the Tuileries Palace near the Louvre in Paris and the royal palace at Versailles as two examples of impressive building entrances. Both included one carriage entrance (eventually translated to the east front of the Capitol) as well as a second facade reserved for splendid views of architecture and greenery (eventually the new west front of the Capitol facing the Mall and Potomac).

The timing of the ongoing congressional advice coincided with stepson John Charles Olmsted’s (JCO) graduation from Yale’s Sheffield Scientific School. In 1875, JCO joined his stepfather in their townhouse on West 46th Street as an assistant. Why not ask John Charles if he would like to take a trip to Europe to study capitols and parks abroad? On a sultry summer day, JCO seemed uninterested in anything (at a time when not every New York building had cooling capability) but soon enough his mother Mary convinced both to try an overseas graduation visit.

John Charles departed in early fall 1877 for a landing in Liverpool and adventures in London’s library and parks, then to Paris to study landscapes and history, visiting his father’s friends and landmarks along the way. FLO joined him in January 1878. It was an excellent six-month education for the son, and an exhausting four months for the father, but one worth every learning experience.

An autumn 1877 letter before FLO set off to join his son reveals a true interest in each other’s success, in the future of the landscape architecture profession, and in foreign travel to enlighten past and future design.

In contrast, FLO’s letters from the same decade to his son Harry, born in 1870 and soon to be renamed Frederick (Rick) Law Olmsted Jr.—while nowhere near the level of intellect and advice on landscape architecture—reveal a fondness and hope for this younger lad, too, whose company he clearly enjoyed. On May 13, 1875, while the family was away traveling in Massachusetts, FLO wrote:

Dear Harry,

The cats keep coming into the yard, six of them every day, and Quiz [perhaps the family dog] drives them out.

If I should send Quiz to you to drive the cows away from your rhubarb he would not be here to drive the cats out of the yard. If six cats should keep coming into the yard every day and not go out, in a week there would be 42 of them and in a month 180 and before you came back before next November, 1260. Then if there should be 1260 cats in the yard before next November half of them at least would have kittens…

Your affectionate father

His older son, John Charles, packing for his European trip in the fall of 1877, received this long and more serious note:

Instructions:

To be read over and committed to memory while at sea, re-read in London and again in Paris.

When you have been out a while write to your mother giving a good account of your voyage and experiences, your ship mates, your sufferings, appetite and news of life. Fill out with P.S. and mail from Cork [Ireland].

If you meet with any accident, of consequence, telegraph.

First business in Liverpool is to see if Mr. Field is in town…

After suggesting additional people to contact abroad, Olmsted advises that John Charles observe the following four directives for his entire trip abroad:

First, You are to search all parks and public grounds for me, taking full notes and writing careful and specific reports…This is not discretionary.

Second, You are to examine zoological gardens and learn the conditions and good arrangements & plans of buildings, paddocks and accommodations for visitors…take notes and be prepared to answer questions when hereafter required. No written report, all discretionary.

Third, Everywhere you are to examine closely and accurately all small architectural objects adapted to park work, pavillions, lodges, entrances, chalets, refreshment stalls, bridges, conservatories, plant stands, fountains, drinking fountains, lamps, flagstaffs, seats, railings, parapets…if you find anything novel and good, especially in plan and arrangement, take sketches and notes and in particular, on return, to make full drawings, all discretionary, of course.

Fourth, Observe general architecture, public and private, with a practical student’s eye, as much as in such a way as (without interfering with other purposes) you will wish you had if you came to be an architect. Discretion.

Three and a half more pages followed the four most important instructions. They included advice on what to look for and bring back to New York (images, maps, analysis and personal reflections of best parks, public and private, keeping in mind the Olmsted’s current work on four Buffalo parks mentioned specifically, as well as French books on landscape design).

It was a tall order for a boy just out of college, but these notes would do for any graduate student just starting in either landscape design or architecture. Fortunately, John Charles saved most of the two dozen 1877 letters (and many more) from his father. JCO’s daughter donated them to the Harvard Graduate School of Design (Loeb) Library for students to still see and study more than a century later.

In his September 14 letter to John Charles, FLO regretted his firmness and inflexible tone. “I am apprehensive that I have [handed out] too much for you to do,” he apologized. His tone was warmer on September 21, asking for JCO’s help to research and find the best examples for the U.S. Capitol work. “I shall have to revise or make an entirely new plan for the terrace and approaches for Capitol over the winter. Get all pictures you can showing terraces, staircases and outbuildings,” he requested.

By October 7, JCO’s first letters from abroad arrived at the New York brownstone home and office on West 46th Street, and his father was most pleased indeed.

Dear John,

I have just reached home from Canada and the East and read your letters from ship board and Chester (latest 23rd). They are in all respects admirable and give us great pleasure…They show that you were well prepared to profit by the journey; better than I had supposed, and I am now sure that it will be of great profit to you in every way. Your notes are just what I want, full and nothing redundant. I look with great interest for what are to follow. I read them all aloud to the family at breakfast this morning.”

Two decades later, after their father’s retirement in the 1890s and working together in the Olmsted Brothers firm in Brookline, Massachusetts, the two sons created the landscape architecture profession within the new American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). John Charles accepted an invitation as the first ASLA president and soon after traveled to the Pacific Northwest, where he spent the next decade designing parks and park systems in Portland, Seattle, and Spokane, as well as work even farther afield in Canada.

New territory for a new profession.

_______________________

By Joan Hockaday, author of Greenscapes: Olmsted’s Pacific Northwest

Next month: The early Boston years of the Olmsted firm