Happy birthday to Frederick Law Olmsted on this 200th anniversary of his birth back on April 26, 1822!

Remembering the new western landscapes, the California mountain trails that father and son climbed together, and the donkey and horseback rides up to Yosemite peaks.

After New York City mayor George Opdyke, representing Eastern investors, gave his hardy farewell to the new Mariposa Estate superintendent in the fall of 1863, Frederick Law Olmsted lost little time packing and catching his steamship to California. The gold-mining estate’s New York trustees hoped Olmsted would rescue the vast former John Fremont estate in the Sierras from ruin and turn it into a thriving gold mining property.

His family would follow with better weather, the next spring. Olmsted’s many letters home gave his family comfort and detailed his progress, reporting the vegetation and landscape along the way, and the San Francisco scene upon his October 11, 1863, arrival.

With previous crossings directly from New York to Liverpool, Olmsted was already a seasoned Atlantic steamboat traveler, but this autumn crossing of the Panama peninsula, a decade before the Panama Canal to America’s West Coast, was a more difficult and disjointed journey, requiring transfers from the Atlantic boat to a Panama jungle train and finally to another Pacific boat. The tropical landscape in Panama caught Olmsted’s eye and curiosity—enough to write his loyal Central Park head gardener Ignaz Anton Pilat with new design ideas.

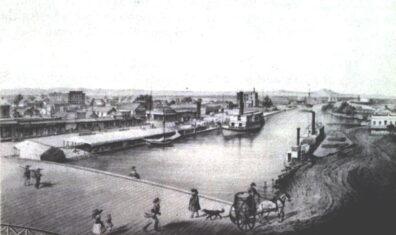

One month after leaving New York, FLO celebrated his arrival in San Francisco at a fine dinner gathering at the popular new Occidental Hotel in the heart of the city. Hosted by Mariposa Estate lawyer (later Mariposa Estate trustee) Frederick Billings of Vermont, FLO’s first few nights were a delightful transition from the exotic and exhausting tropical travel. Billings had traveled to England twice to help Mariposa Estate landowner John Fremont find an overseas investor, with little success. Fremont now lived in New York and was still a trustee of the ranch.

Olmsted and Billings shared landscape ideals. Billings, while a trustee of the College of California across the Bay, invited Olmsted to lay out a college campus on Berkeley’s bare hills, and later urged the city of San Francisco to ask Olmsted to create a park on acres of sand dunes. Olmsted accepted both commissions, and more, during his two-year stay in California.

The Occidental Hotel dinner party also included San Francisco’s respected and influential Unitarian minister Thomas Starr King, whose thriving city congregation included many U.S. Sanitary Commission supporters as well as California governor Frederick Low, who would eventually ask Olmsted to serve as chair of a Yosemite Park land-planning commission.

Olmsted found himself surrounded by old and new friends with shared interests in landscapes east and west, and, unexpectedly, fine food and fruit: “I have been on the streets this morning,” he wrote his wife Mary on October 13, just before heading for the mountain estate with Mr. Billings. “It is New York, East and West shook together,” with very few older residents, he noted. “The most striking thing is the great fruit. It is really wonderful—the size and fairness of it—when seen in such large quantities…The Apple-women on the streets….have fruit that would create excitement at Covent Garden [London’s famous fruit and vegetable market]….I ate the best grapes I ever tasted this morning….” he gushed and guessed at California’s future farming sensation soon to emerge after gold rush days.

The next week, Billings escorted Olmsted through the entire Mariposa Estate up in the Sierra. Traveling by riverboat, stagecoach, and horseback, Olmsted realized the extent and enormity of the mission, yet his journey produced this evaluation:

“From the moment I delivered your letter, he gave every hour of his time to his instruction and assistance until he left here this morning,” Olmsted wrote the Mariposa Company president and trustees back in New York. Mr. Billings’ information and suggestions “will be of great service to the Company and I hope that you will know it is appreciated.” Decades later, as president of the Northern Pacific Railway, Billings invited Olmsted to lay out their western terminus in Tacoma, Washington.

Settled into the Bear Valley headquarters above the company store, Olmsted studied new ways to improve the estate’s different mines and towns. Searching for a better water supply and a possible canal for Mariposa, he and engineers traveled 20 miles up the middle fork of the Merced River. Stunned by the beautiful scenery, he wrote his wife on November 20, 1863:

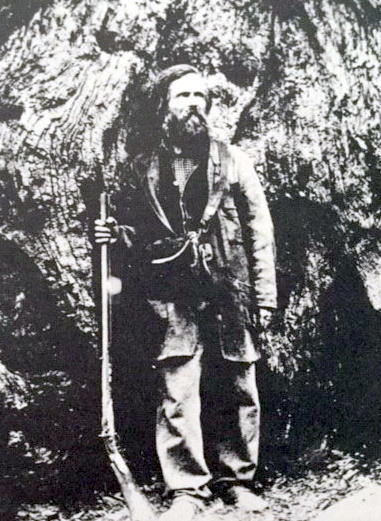

“I had a highly interesting journey in the mountains—exploring the South Fork [of the Merced River]. We passed through the Big Tree Grove. The big trees are in a dense forest of other trees, a few standing free. They don’t strike you as monsters at all but simply as the grandest tall trees you ever saw…You recognize them as soon as your eye falls on them, far away, not merely from the size of the trunk but its remarkable color—a cinnamon color, very elegant.” Olmsted promised family trips to show them the “Big Trees”—Sequoia gigantea—the grove found and named by nearby ranch owner Galen Clark. Olmsted admired Clark, and after his family arrived, spent time the next two summers camping at and enjoying Clark’s Ranch. Now known as Wawona, it is a popular tourist stop on the way to the Yosemite Valley.

In March 1864, U.S. Congressman John Conness and colleagues debated setting aside the California Big Tree grove of giant redwoods and the nearby Yosemite Valley as a preserved landscape for the public. President Lincoln signed the bill on June 30, 1864. Governor Low appointed eight men to advise California on managing the great land grant. One was Frederick Law Olmsted. He became its working chairman in 1865.

From the moment Olmsted took his chair on the Yosemite commission, his priorities in California shifted. He found a more lasting California legacy than gold—preserving this landscape so handsomely and naturally designed, it did not need a landscape architect.

Survey crews and local dignitaries followed. Fall was the perfect time to visit the high country, as the heat of the summer in Bear Valley gave way to cool days and even cooler nights up in the Sierra slopes. His father arranged for John Charles Olmsted, now eleven and the oldest of the children, to accompany him, a small survey crew, and Yale Sheffield Scientific School’s professor William Henry Brewer, to a high point in the park’s eastern edge. It was the chance of a lifetime to be at the top of Yosemite peaks yet to be named and absorb the astonishing view. Brewer later wrote in his pocket diary: “it was a charming trip…enjoyed the scenery of that grand region. Mr. Olmsted is a very genial companion and I enjoyed it.”

After the family’s Yosemite summer encampment, Olmsted wrote his own father back in Connecticut on September 14, 1864, from Bear Valley:

“We returned here last week from the mountains…Mary and the children had been in camp seven weeks, the last month in Yosemite…we found it much more beautiful than we had been led to anticipate…the children enjoyed the life very much and seemed to gain health daily.”

He then told his father about a 6-day pack-mule adventure in and above Yosemite, far from the family campsite near the Yosemite Falls: “John accompanied me in my journey to the Eastward and we had with us Professor Brewer of the State Geological Survey (and lately appointed professor of practical agriculture at Yale College)…the first day out of the Valley we reached an elevation of nine thousand feet and came a little below this for a week…with John and the Professor walking, and I riding, ascended a mountain…over 12,500 feet above the level of the sea.”

The altitude had little effect on the travelers, FLO reported to his father: “We nevertheless suffered scarcely from cold or rarified air…the view to the Eastward was very fine…” And as the snow finally disappeared near their mountain encampment, father FLO reported: “John went down on the East side to a bank and brought us a snow-ball for dinner.”

Professor Brewer remained with the Yale Sheffield Scientific School for the remainder of his career, and by no coincidence, John Charles Olmsted studied and graduated from that school a decade later. Brewer visited Olmsted’s family in Connecticut soon after his California survey years and brought them some handsome Watkins photographs of the Yosemite Valley as a reminder of their delightful camping days out west. FLO was allowed the privilege to name the high peak after his U.S. Sanitary Commission colleague Oliver Wolcott Gibbs, distinguished professor of chemistry at Harvard.

For John Charles, did the memory of that week near the top of newly-named Mt. Gibbs prompt him to include the Mount Rainier vista into the University of Washington campus plan more than 40 years later? Did the Yosemite peak views match, in his mind, the majestic Olympic Mountain site across the Seattle waterfront? To see the true value of extraordinary landscapes so early in his climbing career was a rare moment for any boy.

Meanwhile, the Olmsted’s governess (and an amateur botanist), 52-year-old Miss Harriet Errington, camping in the valley by the waterfall with the other Olmsted children, was equally in awe. She shared her keen interest in landscape and botanical study in long letters to her English and Staten Island family members, now preserved at the Newberry Library in Chicago, and during daily three-hour lessons for the Olmsted children.

Olmsted’s 1865 detailed report on the Yosemite holdings was lost for decades after a minority of members worried about submitting such a big bill to the state of California. Western bankers never blamed Olmsted for mining company failures or the pending legal proceedings against previous estate claims. In 1865, while awaiting word from eastern bankers and trustees on new investors to save the holdings, the estate’s San Francisco bankers at the Bank of California office asked Olmsted for personal landscape design advice. Bank of California president Darius Ogden Mills asked Olmsted for suggestions on design, plantings, and a name for his vast Peninsula estate. “Millbrae” was the final choice, a title that lasted longer than the plantings planned for the now-scattered estate holdings. Peninsula rancher and Bank of California investor George Henry Howard asked Olmsted to come visit his Rancho San Mateo estate. Later, from New York, Olmsted sent a shipment of plants and trees for the estate. New investors, the Dodge Brothers, came on board in 1865, leaving Olmsted to ponder his future, either in California or back East. Through dozens of letters, Central Park architect Calvert Vaux convinced FLO to return East to plan parks and estates together.

During his last days in San Francisco, Olmsted met with the mayor to elaborate on his proposal to create a vast city park on the drifting sand dunes between the Pacific Ocean and the thriving city inland. In the August 4, 1865, San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin, Olmsted eloquently urged the city to create the park before time ran out.

“It should be considered and acted upon now—San Francisco ought to profit by the example of other cities,” Olmsted wrote. He had learned much from New York’s Central Park and other attempts nationwide to preserve landscapes and create quiet, contemplative spaces in the heart of an emerging city’s busy and noisy surroundings.

The mayor promised he would ask FLO to send a detailed city park report to expand on the newspaper editorial once he reached New York and unpacked, and the written request arrived in New York three months later. By then, Olmsted and Vaux had set up their office and were planning their Brooklyn Prospect Park design. Far away from the Pacific sand dunes, Olmsted quickly produced the San Francisco park report. (Next month we’ll explore the city response to Olmsted’s plea and detailed plan, as well as other western works he completed after his fall 1865 departure.)

FLO’s two years in California were productive indeed—even when the gold diggings and investments disappointed. He found meaningful landscape design and preservation work, and with help from former architect partner Calvert Vaux and new western parks enthusiasts in Yosemite, launched his professional landscape architecture career.

_______________________

By Joan Hockaday, author of Greenscapes: Olmsted’s Pacific Northwest

Next month, FLO and family return to the East to begin the early practice of landscape architecture and craft a new profession.