Two Olmsted sons—John Charles and Rick—step in to continue their father’s legacy, and help create the landscape architecture profession in America

___________________________

Frederick Law Olmsted (FLO), now in his 70s, tried unsuccessfully to slow down. Clients kept calling, asking for design help with new university sites and grand private estates from Maine to California. With park work also continuing in Boston and many other cities, his sons back home in the Brookline, Massachusetts, office worried their father was overextended. Then, in the mid-1890s, the focus shifted to the four greatest and most important works of Olmsted’s long career.

The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 design commission came in quietly, but brought lasting fame and success when Olmsted was summoned to Chicago to work with architect Daniel Burnham on the master site design along Lake Michigan.

George W. Vanderbilt’s Biltmore estate, created out of the magnificent Asheville, North Carolina, forest property, occupied FLO’s travel and working days before and after the Chicago World’s Fair opened on May 1, 1893.

The Stanford University campus work came to a close in the early 1890s. An October 2, 1891 New York Times headline read, “Stanford University Opened.” Olmsted wrote Stanford on October 28th, “I congratulate you and Mrs. Stanford with all my heart…I hope that you understand….our connection with your noble undertaking should continue.” Leland Stanford replied on November 9, 1891, thanking Olmsted and adding, “We are gradually improving the grounds in accordance with your plans.” Standford’s response contained no mention of FLO’s offer, and after Stanford’s death in 1893, Mrs. Stanford’s brother Ariel Lathrop came to be firmly in charge of the ground’s western campus improvements. As the campus grew beyond its original bounds, little hope for an Olmsted office reconnection surfaced.

The U.S. Capitol building and grounds re-design were also finally finished, but with Olmsted’s greatest supporters (especially Vermont Senator Justin Smith Morrill) still installed on the Senate committee that started Olmsted’s task two decades earlier, the Olmsted firm moved on to their next Washington, DC design suggestions at American University and the National Zoo, and more DC assignments soon followed.

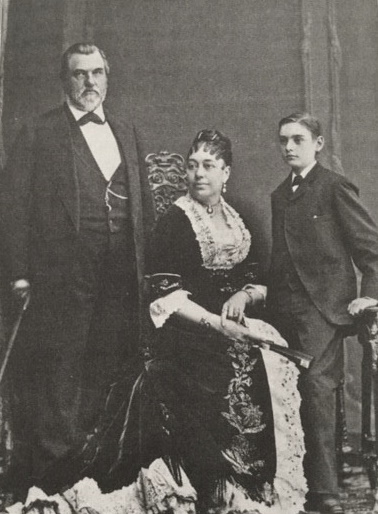

Older son John Charles Olmsted continued managing the growing Brookline office while his father traveled extensively to meet clients and demands. Sadly, new partner Harry Sargent Codman, the lead partner on the Chicago Fair work, fell ill and died during crucial Chicago Fair design planning in 1893, leaving Olmsted to quickly fill in. John Charles Olmsted became an increasingly valuable office manager for his father, keeping office correspondence, apprentices, and the new client demands in order.

Meanwhile, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., (Rick) continued his Harvard studies, working toward his 1894 magna cum laude degree. FLO hoped to educate his younger son in professional landscape architecture studies before Rick finished at Harvard program—or even took his first Harvard class. In 1890, he asked his Chicago Fair architecture counterpart, Daniel Burnham, if Rick might fit into Burnham’s Chicago office summer internship. Burnham approved and gave Olmsted’s son some summer space in Chicago before the Exposition opened. Following the family tradition of showing his sons European sites, in the summer of 1892 FLO took Rick to old Parisian world’s fair locations and to Thames River waterside sites, studying boating and vegetation for Chicago World’s Fair design ideas.

The Chicago Fair eventually settled on a wooded island of Olmsted’s design directly in the middle of the formal architectural buildings lined up along Lake Michigan, where Olmsted’s scenery enhancements would offset their severity. At an architect’s dinner in March 1893, Burnham praised Olmsted and offered credit, “in a broad sense…of the design of the whole work” for the Jackson Park fair site.

Soon park districts across America called on Olmsted for advice and design ideas, and he admitted the public work was of more value to him, personally, than all the private estate work which also increased substantially during his later years. Above all, the Boston park system occupied his last years in Brookline. The one exception was George W. Vanderbilt’s private Biltmore estate, since the final landscape design was also for public education and enjoyment, with the Biltmore Village design addition down the road. Vanderbilt, like Burnham, was an Olmsted admirer. Forty years his senior, Olmsted had a “truly big and lovable nature,” Vanderbilt wrote to Olmsted’s sons years later. Handsome portraits of Olmsted and architect Richard Morris Hunt by artist John Singer Sargent still hang on the wall at Biltmore, Vanderbilt’s last support gesture for the estate’s two designers.

But the frequent train travel was exhausting for the senior Olmsted, and by the mid-1890s, his many letters to John Charles and Rick began to show his apprehension and present realistic plans for the firm to continue should he become incapacitated. In a May 10, 1895 letter from Biltmore, FLO hinted to John Charles about the Olmsted firm’s future changing of the guard:

“It has today for the first time, become evident to me that my memory as to recent occurrences is no longer to be trusted…I suppose that I am a little affected physically, as I always have been in previous visits, by the elevation of this place [Biltmore estate] but I do not think that I can rightly conceal from you the fact that I am more distrustful of myself than I have ever before been…”

He then asked John Charles for partner help on jobs of “considerable importance.” The end was near and if possible, his sons were ready to help their father retire with dignity. At first, keeping FLO away from the office was awkward. A brief stay on Deer Isle, Maine, followed by a European winter with members of his family, failed to permanently solve the problem of their father’s failing memory. From Deer Isle, FLO wrote his partners:

“My will was drawn up some ten years ago…You, John are dealt with as my elder son, partner, and designated successor. Rick’s professional education is provided for and it is presumed that he will be partner with you…”

Indeed, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. did eventually join his brother in the firm, renamed Olmsted Brothers after the turn of the century, and both helped create the professional standing of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). Later, each brother found new landscape work on the West Coast—John Charles in the Pacific Northwest, and Rick on the Palos Verdes Peninsula in Southern California. After a half-century of carrying on his father’s legacy, Rick retired permanently to Palo Alto, where in 1886, he and his father had traveled by cross-country train to visit the Stanford University campus site. During his West Coast travels, John Charles sent vivid letters home chronicling his landscape architecture successes. He married a Brookline neighbor in 1899 and finally retired to the same Massachusetts suburb where in 1874, he and his father had created a new office briefly called F.L. and J.C. Olmsted—just one of many monikers. Prior to his death in 1903, Frederick Law Olmsted lived his quiet last years at the McLean Hospital in nearby Belmont, Massachusetts.

Now a National Park Service property, the original Brookline, Massachusetts, Olmsted office is accessible to visitors, preserving FLO’s—and his sons’—life’s work.

___________________________

By Joan Hockaday, author of Greenscapes: Olmsted’s Pacific Northwest