To honor our health care professionals and other essential frontline workers during this trying time, we are posting a chapter from Rugged Mercy, about a western frontier doctor who exemplified rugged courage and devoted compassion, and who—like our modern heroes—risked his own life on multiple occasions. We hope you enjoy reading.

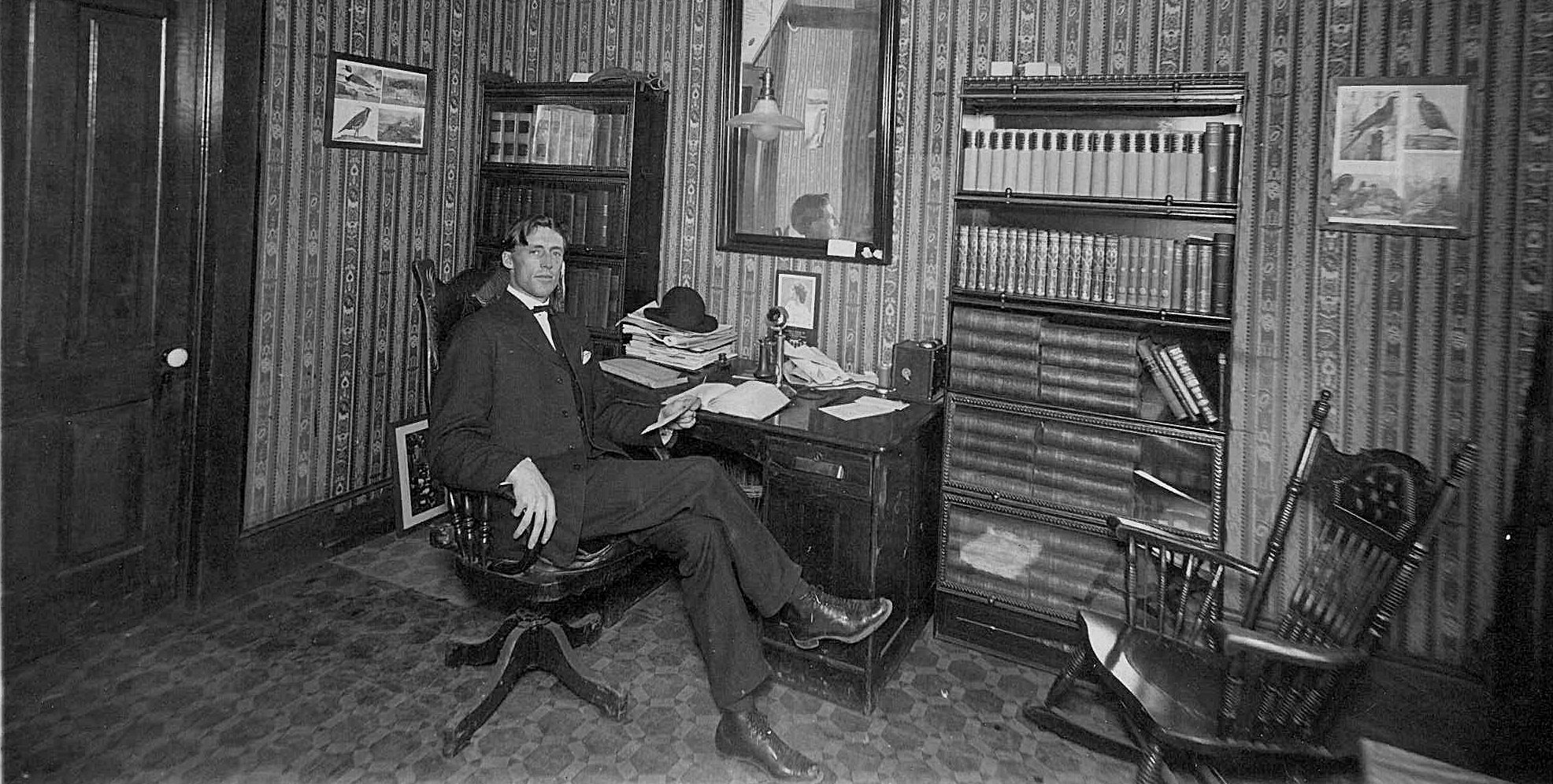

The photo above, taken in the early 1900s, shows Dr. Wright in his office.

The Placenta Previa Case

Hailey, Idaho

1908

This time the outcome would be different. In the valley the night snow was floating to the earth in huge flakes, in magical silence. But in the canyons it was fairly screaming out of the sky, up where the mountainsides narrow and the slopes steepen. Tiny ice pellets. Stinging bullets driven by a furious wind. The wind bore deep into the side of his face, into the bones of his skull, the nerves of his rugged jaw and forehead. It was the devil himself up on that mountain ridge, trying to keep him from his chance at redemption. An unborn child was losing its lifeline—the very same emergency he’d faced back in Missouri. The placenta, the coupler to the blood supply, was beginning to detach from the uterine wall. Soon, the baby’s only source of oxygenated blood would be spilling uselessly elsewhere, leaving the trapped child struggling for breath while still in the womb. And its young mother, also deprived of blood, would die.

The call had come an hour before the January storm took down the phone lines. It had come from Leff Shaw, the ranger up at Warm Springs. “John Stewart just snowshoed down from his place,” he reported. “Says it’s his wife’s time. I don’t know, Doc, this one don’t sound right to me. Says she’s bleeding. That normal, Doc?”

“Let me talk to him.”

John Stewart came on. He said that the contractions were coming, and that there was blood.

“All right, here’s what I want you to do. I want you to get back up there and make sure she doesn’t get out of that bed, not even to pee. Now you go do that. I’m on my way.”

John was out of breath, probably from the wide leg trot required to make good time on snowshoes. “What’s wrong with her Doc? What’s goin’ on?”

“Well, John, bleeding isn’t good. I’m going to need to get up there right away.”

There was the dull acceptance of misfortune in John’s voice, also a pleading. “Doc, you ain’t gonna make it. Ain’t nobody can make it up here in this storm, now that the sun’s goin’ down and the wind’s a startin’ to kick up. I barely made it, and I had the light of day.”

“I’ll make it.”

“Doc, in two hours you won’t be able to see your hand in front of your face…”

“Now you listen to me, John. I will make it. I’ll use the light sleigh. I’ll have the livery rig it with a four-horse team. And Leff there can outfit me with his dog team for the second half of the trip, have it ready and waiting at the ranger station. Believe me John, I will make it.”

“Doc, hug the creek. Stay away from them mountainsides. Slides are comin’ down.”

“John, I need you to hold yourself together. I’ll be coming up there by myself and I’m going to need some help. I can’t have you falling apart on me.”

“Be careful Doc. Hear? I’ll put a lantern out.”

“Now John, here’s what I want you to do. You go back there. You tell her I’m coming. But you tell her in such a way that keeps her calm. I want you to hold her hand, tell her things are going to be fine, tell her whatever you have to tell her, just keep her calm. If she’s calm the bleed- ing will be slower. And don’t let her get up out of that bed. Whatever you do, don’t let her get out of that bed. John, one more thing. I want you to boil strips of rags for me and dry them before the fire. Long strips. Long cloth strips. New clothes, old clothes, I don’t care. Just boil them. And have some water boiling for me when I get there.” Bob always stood when he talked on the phone, when there were urgent things to be said, holding the thin bronze stand in one hand and the black ear piece in the other. He paced back and forth the distance of the cord, ten or twelve feet from where the phone normally sat on the corner of his desk, by a stack of books and papers upon which lay his derby hat.

The office was small. Outside there was a sign tipped with a wedge of new fallen snow that read “Dr. Plumer and Wright.” A similar cap of snow sat on top of the iron hitching post in front of the snow-covered boardwalk. Jim, the boy who helped out, had begun to shovel again. Four more inches had accumulated. It had been snowing since noon. In all, including previous snowfalls, five feet lay on the valley floor.

The move back to Idaho had come quickly. First they moved to Meridian, a small town outside of Boise. Two weeks later, with the paint barely dry on the sign outside Bob’s new office, a cable came from Dr. Plumer in Hailey offering a partnership—a gift from God with built-in patients, guaranteed food on the table, and 30 percent of an existing business.

It worked for Dr. Plumer as well. Bob quickly established himself, tripling the business. Bob had a gift for healing, particularly when it came to children. He was continually traveling back east to the Mayo Clinic for post-graduate work in the diseases of children, and to Chicago’s Cook County Hospital for surgical residency. Cook County was staffed with the best in the field of surgical medicine, and had a continual inflow of trauma patients. It was like a processing plant—construction accident victims, surgical emergencies, gunshot wounds, knife wounds. This experience, combined with his mastery of anatomy, gave him a reputation no other doctor could match. Whenever there was a child with a broken bone, Bob was almost always called, even by other physicians. When an appendectomy was needed, Bob was the one they summoned. He was known as the doctor who never lost a patient. No one knew about the Missouri tragedy.

It would not happen again. He was wishing it was tomorrow, because then he would be looking back on his victory.

“I’m on my way John.”

“You really are gonna make it, aren’t you Doc?” “You bet I will. Your Mary’s going to be fine…”

He slapped the reigns again, to drive the lead horses through a barrier of drifting snow, and pulled his high collar further over the side of his face…and shivered way down deep, not from the cold, but from having made such a promise.

The bobsleigh jerked as the lead horses finally broke through. The sleigh’s skis had been forged from foot-wide strips of metal. The rear runners had been detached so that it could move about with the ease of a two-wheel buggy balanced by the yoke and horse. Up ahead, he thought he could see what might be the flickering lights of the ranger station.

He’d already come about fifteen miles, he figured, following the railroad tracks to Ketchum where Sid Venables had been waiting with a fresh team, then veering off into Warm Springs Canyon. Each one of those miles had become more difficult to travel, more impassable, each one buried deeper in blowing and drifting snow. And with each passing minute the sky was growing darker and the air colder. He was well- shielded—thick clothes and gloves, woolen hat with earflaps, horsehide coat—it gave him a feeling of power against nature’s onslaught. Ahead of him was the protection of four massively muscled and loyal beasts, relentlessly pushing forward, pulling, protecting. Nothing could stand before their awesome strength.

But as the minutes went by the horses began to struggle. Their sides were heaving brutally, their nostrils flaring as they sucked in the cold air. The ranger station would be their limit. The light he thought was from the ranger station was gone. Soon it reappeared, then was gone again, then came back, then gone again.

Eventually the light split and became two lights, then three, each from one of the windows. And carried upon the screaming wind came the barking and wailing of the waiting dogs.

The snow had drifted up to the windows, all the way up to the roof on one end. One window was half covered by a drift. The wind was fearful now, with an empty sound, a roar that couldn’t be silenced, rushing with merciless speed through the evergreens and the naked aspens, breaking at times into a scream. The edge of the ranger’s roof was flapping against the side of the building, and suddenly flew off into the dark. The roof was single sloped and steep, with the back wall inset into the hillside like a bunker, and covered with a good two feet of unshoveled snow. The dark outlines of two larger buildings, unlit, were silhouetted on the other side.

Two figures emerged from the warmth inside, Leff Shaw and his wife Mary-Ellen, wearing sealskin parkas and fur hide mittens and mukluks. “Come on in and warm ye’ self, Doc.” In the old days Leff used to run a team in and out of the Hudson’s Bay Company, carrying mail and freight. There was nobody better at driving dogs than Leff.

“Can’t spare the time, Leff,” said Bob, shouting through the wind as he climbed down from the front seat of the sleigh. “This one’s urgent, real urgent.”

Leff looked up into Bob’s face with concern. “Doc—ye might want to think about letting this one go. Plain truth is, yee’re not going to make it out there. Ye’d need to be half wolf to survive out there in this storm. To tell you the truth, Doc, I haven’t convinced myself I want to risk my dogs either, on something that can’t be done.”

Bob spoke loudly, through the rigidness of his wind-shorn jaw, and stared so hard at Leff that it frightened the little man. “With or without your team, I’m going,” he stated. Then, after seconds of only the sound of the wind, he said in a gentler voice, “Leff—it’s just something that has to be done.”

“OK, Doc, I’m comin’ with ye then. Mary-Ellen will board down and water yeer team. I’ll take ye as far as Board’s Saw Mill. While I’m gettin’ yeer bags hitched onto the sled, ye go ahead and go inside and get a swaller or two of coffee. Go on now, hear? It’s on the stove. Ye go do it. Yee’ll want to dry those hands and gloves out a bit. The worst of it lies ahead.” “All right, Leff. Five minutes. There’s three bags there. I need them all.”

The shoveled out pathway to Leff ’s front door was drifted over, visible only as an indentation closer in to the building; the two sets of fresh footprints were already beginning to disappear. The door was made of thick beams of timber covered with canvas. Bob had to kick snow from its base to open it. Inside was refuge. Two coal oil lanterns burned on a rustic table that had been hewn from the trunk of a tree. From a cast iron cook stove emanated a wave of heat that flushed Bob’s face. On the stovetop beside the hook-handle used for lifting the lids was a coffee pot. He poured some into an iron cup; its heat was euphoric inside his belly.

Before the ice on his turned-up collar could melt he was back outside, cradling the steaming cup, sipping its magical brew. Leff was pulling the last strand of rope through the sled, tying it over the bags, throwing it into a final half hitch. The sled, of flexible birch wood, was about ten feet long. Its parts were lashed together with rawhide thongs to give it flexibility when moving over bumps and around curves. A bendable u-shaped piece was fashioned over the brush bow in front to give the trailbreaker a handle while kneeling for a ride, or for enclosing a passenger within a canopy, or, for night travel, a place where a lantern could be lashed.

They were ready. “Maw-Shaaaay,” yelled Leff, a word resembling the French word for go, and the team rose. The lead dog jerked against the tug lines, the signal for the other five dogs to pull. Leff was anchor and push man. Bob ran ahead on snowshoes to break down the deep snow for the lead dog, slapping along at a fast walk, an awkward trot. Two fools. Two courageous fools, disappearing into the night, the lantern bouncing, twinkling, the last thing to be seen.

If Mary-Ellen was worried for her husband’s safety, she didn’t show it. As the sled broke into a glide she simply continued unhitching the horses, barely looking up. Surely though, terror must have gripped her, for a moment at least, upon seeing them blend into the blackness, upon hearing the wind swallow up the sound of the dogs.

Back at home, in their small two-bedroom home on Main Street, Dott was preparing dinner, to be served whenever Bob returned. She was melting snow in a big tin bucket on the stovetop. The pump outside had been frozen for days. On their oval kitchen table, the same table they had back in Missouri, was a cup of sifted wheat flower and a half-cup of sugar, and an empty mixing bowl. She was making Poor Man’s Pudding. Then she’d make hot biscuits and dried sweet corn, then panned chops. Or maybe brown beef stew. That would be easier to keep warm until Bob’s return. She knew Bob could always stop in at Fat’s Chinese restaurant down on River Street on his way home, have Fat fry him up a steak. But this was something Dott needed to do. It kept her mind occupied. Her thoughts tended to form their own patterns, diabolical scenarios of what could happen to a man out there on a night like this, everything from wolves to snow slides to just plain freezing to death. The mind seems to move that way, creating mechanisms for its own misery. In that misery, strangely, it seems to find comfort.

“The Good Lord watches out for our doctors,” Mrs. Plumer had told her. Dott and Mrs. Plumer had become close friends.

“Be careful, I’ll pray for you,” Dott had said when Bob flew out the front door. “I’ll have a hot meal waiting…”

“Pray for Mary Stewart,” he called back. “She’s the one who needs a miracle.”

She prayed for both.

Bob and Leff were traveling the edge of the creek bed, using its smooth expanse of snow and ice as a navigational highway. They could see steam rise from its center, could feel it as it came spiraling up. Warm Springs Creek was the size of a small river, really, thirty to fifty feet across in spots, and had enough of a flow to keep it free of ice in the middle. “Best way to move about in winter,” Leff always said.

The dogs were finally running in precision. For the first mile or so they snapped and snarled at each other, stopping, starting, and tangled themselves in the lines. Then they settled down and began to pull, heads low, tails arched, muscles straining beneath their sheltering fur. The dogs were a mix of breeds, all large dogs—a couple of bird dogs, a collie, a hound, even a half wolf. The half wolf, Jake was his name, looked more like a floppy eared black lab than a wolf. He was the wheel dog, the first in front of the sled, the most important position on a team, responsible for the first tug, responsible for the initiation and steering of a turn, responsible for keeping the first length of line tight and the other dogs moving. The dogs were hitched single file, six long, connected by tug lines threaded on each side through a harness similar to the yoke of a horse, fitting over the shoulders and around the front legs.

The journey was uphill, and though the grade was for the most part gradual, imperceptible to the eye in most places, its rise was significant, almost a thousand feet in the ten remaining miles of the journey, and it was exacting its toll on the dogs as they slogged through the deep snow. Bob and Leff chose to run and push. Perhaps they could have ridden, driver and passenger. Perhaps the dogs could have pulled them, but it wasn’t worth the risk. There is a point of refusal beyond which a team will go no further. They simply lay down and quit. When that happens, all a driver can do is rest them and wait.

Their travel was mostly through deep snow. Sometimes the freezing drifts were crusted over, and then Bob and Leff could both ride. At one point they came to a backwash—Bob thought he recognized it as one of his favorite fishing holes, too deep underneath to trust the ice—and had to leave the streambed through a narrow cliff-like passage between two stands of thick trunked cottonwoods and aspens. They had to unleash the dogs and help them along one by one, then, with Jake’s help, rope the sled up.

“A horse would die out here,” boasted Leff. “Smaller and weaker a dog may be, but out here a dog is the most powerful thing there be. Especially this one.” He ruffled Jake’s head.

“The creek, she’s a windin’ in closer to the mountain, Doc,” Leff observed. “Best stay off her for a time. Best stay clear a’ them slides. Otherwise they won’t find us until the spring thaw. Best travel the brush awhile.” Leff couldn’t see the mountainside but knew it was there, cliff-like in some places. He knew exactly how far they were from the mountain at any given time by the twists and bends of the river, and by the size and types of trees that grew on its bank. “If’n we head straight yonder we’ll meet up with her again ‘bout two mile down.” Leff pointed into the snow, to somewhere, as if he had vision that could pierce the storm. “Then, quarter mile more, where the creek crosses to the north, we should come to the saw mill.”

“Ye need to spell me awhile Doc,” he said. “I’m not as young as I used to be.”

Bob was a respectable driver himself. He’d made at least a dozen trips using Leff ’s team, though never under conditions such as these. He rattled the drive bow and shook the sled. The dogs came to their feet. “Maw-Shayyy!” he yelled. The dogs jerked forward obediently. When a smooth glide was established he yelled, “GEEEEE!” to steer them to the right and toward where Leff promised was the correct course. They were traversing the canyon rise and the snow was crisp, so the sled ran easy, and when the dogs were up to speed Bob rode the runners and Leff kneeled on the brush bow.

“Now steer ’er a might that way,” said Leff, pointing, as barren aspen trees began to appear around them.

“HAWWW!” yelled Bob, and Jake and the lead dog pulled to the left, and the team dogs followed.

“Best damn wheeler on the continent, that dog be,” said Leff.

Soon the security of the creek was behind them and they were alone in the confusing maze of the valley, thick with trees, evergreens, cotton- woods, and aspens. Minutes seemed frighteningly like hours. The sage- brush and rocks and fences that in summer made the land recognizable and habitable were all slumbering beneath six feet of snow, twenty or more at the apex of the drifts—tree top level. Finally they saw it. Steam. They were once again at the creek. They bore left onto the creek bed, and twenty minutes later they came to lights. Board’s Saw Mill.

Minnie Board was gracious. She knew they were coming and had hot coffee and sandwiches waiting. Someone had phoned her before the lines went down. She’d put lanterns in every room of the main house to guide them in.

Minnie was a young woman, nineteen or twenty, and pretty. She was so bundled in clothes and scarves her eyes were barely peeking out. She offered a room. “You should stay the night, Doctor Wright. And go on in the morning.”

“Thanks Minnie, but I gotta keep goin’. Leff will be taking you up on your offer, I expect.”

Said Leff, gobbling the sandwich and gulping coffee, “Doc, listen— what we’ve been through—a Sunday picnic compared to what’s up ahead. Yee’re not going to be much good to that woman and her baby if ’n you end up lost and froze to death.”

“Leff, if I wait and go tomorrow you just as well send Ralph Harris in my place.” Ralph was the undertaker.

Offered Minnie, “Least ways, Doctor Wright, you can come in and warm yourself a spell.”

“—I suppose I do need to put some feeling back in these fingers of mine. Working fingers are something I’m going to need up there.”

Minnie’s place was wrapped almost entirely in snow. It was a long log house with barely the tip of it showing. Sliding snow from the roof was packed to the eaves on the south side, and on the north side drifting snow sloped all the way to the roof’s apex. A path deeper than a person’s head had been hewn down to the door. It looked like an entrance to an underground potato shed with steps sculpted into the ice so perfectly they could have been done by an artist.

Flames roared inside a large floor-to-ceiling stone fireplace. Bob pulled off two sets of gloves and rubbed his hands together, and held them before the wonderfully warm fire.

Five minutes was all he could spare. Even that might be too long.

Seconds could make the difference. Minnie gave him a large set of cowhide mittens to put over his own gloves. “These here’ll keep you so toasty you won’t never need a fire again,” she said. She wrapped one of her wool scarves around his face. “You keep this on too. You’re gettin’ one a’ them spots.” He’d once treated her for frostbite on her nose, a white spot the size of a dime, a circular dot of frozen flesh.

Leff instructed, “Back track to the creek, then follow it westward up the canyon till you come to a cottonwood. Big cottonwood. Trunk the size of a polar bear’s chest. That’ll be Warfield Hot Springs. Cain’t miss it. Then ye turns left to the road. Ye can tell you’re at the road because of the tall sticks John has put up to mark it. Ye should be able to see the tops of them, and the lantern he’s hung there.”

Leff followed Bob out to the sled to talk privately. “If anything hap- pens to any of them dogs, if ’n one comes up lame, I want you to use your piece. Ye got a piece in there? Right Doc? Doc?”

“Your dogs will be fine, Leff.”

“Doc, ye promise me. I don’t want no lame dog comin’ back here. A lame dog ain’t no use to me. Ye promise me ye won’t bring me back no lame dog.”

Bob turned toward the sled without responding.

“Second thought, Doc, don’t shoot it. The sound will bring a slide down. Use that big knife of yourn. Cut its jugular real quick, so’s it won’t suffer.”

“Nothing is going to happen to your dogs, Leff.” “I’m just sayin’—”

“I’ll take good care of them.”

“It’s hard goin’ out there. They could get hurt. I don’t want any lame dogs comin’ back and I don’t want you to leave any of them out there to get froze.”

“I’ll be fine. Your dogs will be fine.”

Bob seemed powerful as he pulled away, and Leff and Minnie were believing he would make it.

He moved faster than he expected he would, once the dogs stopped their bickering and augured in, traveling along the creek bed snowfield once again, running, pushing, gliding when they could.

The pounding in his chest made him feel strong, the thrashing of his heart, its powerful flexing as it sent blood surging through his limbs, tingling them with warmth. His hands were so warm he didn’t need the mittens anymore. He felt a bead of sweat begin to roll down his right cheek. The body provides its own heat, if worked vigorously enough.

Then fear electrified him.

He yelled, “HO,” for the dogs to stop, and he set the snow hook. A warm wind was hitting his face.

A Chinook!

The ghostly blow from the north. A thing that cannot exist. The devil wind.

Legend only, some would have you believe, Indian folklore, the tales of the midnight wind, a blanket of heat rolling in out of the north in the ice-dead of winter.

Most of the falling snow had stopped. What was left was whirling about on bits and pieces of leftover sky, dying formations of low, fast moving clouds, black clouds, drifting air behind which lay the withdrawn storm system. It was a fury that was now locked within a massive, dor- mant cloud dome.

It was a wind that no longer howled, a wind that was deceptively quiet, that sifted through the treetops with a muffled roar, a wind warm enough to turn the bulletproof ice beneath his feet to mush and the mountainsides to butter.

“GEEEE,” he yelled, and rolled the dogs to the right to get them off the creek bed. He cracked the whip and yelled for them to run.

The dogs perceived the danger also, for they ran furiously up the embankment. Beneath their movement could be heard hollow cracking sounds.

In minutes, perhaps seconds, the creek bed would be a death trap of slush. Frozen quicksand.

There was just enough light—snow reflects light off the sky of a snowstorm, somehow, from somewhere—for him to see the creek bed in back of him. It was rolling like it was in some kind of earthquake.

He’d made it. He thought.

He heard the whipsaw of trees and the breaking of timber from the slopes of the mountain. At first it wasn’t a concern because the mountainside was several hundred yards away, a half-mile maybe, and across the creek. But a look in the direction of the sound stopped his breath. A smoky white cloud was consuming the entire side of Bald Mountain, swallowing trees and blowing their crushed bits into the air like so many sticks of kindling. He’d never seen anything like it.

His mind froze. The dogs sensed his confusion and stopped completely, losing precious life saving seconds. He rocked and pushed the sled to jar it free; loose snowpack tends to grab the runners during even the briefest of stops. “GO! MAW-SHAY! GO! MAW-SHAYYYY”

The start was hard. The snow was excessively heavy and wet from the winds of the Chinook. The dogs strained and yelped and whined. With Bob’s help they managed to lurch it forward.

He reached for the whip and began cracking it above their heads— “MAW-SHAY, YOU CRAZY HOUNDS. MAW-SHAY.”—and pushed—and pushed—.

The avalanche, massive, a forty-foot wall of snow, was sweeping across the entire valley.

He and the dogs were gliding now, moving fast, but he could feel the monster behind him, gaining. It was like trying to outrun a locomotive. To his right was the crest of a ridge. Safety. “HAWWWW,” he yelled. “HAWWWW. COME HAWWWW.” If they could just climb it in time. The turn was so abrupt the sled tipped and the two lead dogs tangled themselves in the lines. Bob unsheathed his knife and cut them loose and righted the sled, and yelled for Jake and the remaining three dogs to pull. “PULLLL. PULLLL. PULLL. MAW-SHAY.”

At the top of the ridge was a wind blown cornice, itself a recipe for a slide. The avalanche would follow the contour of the land. If they could get high enough it would pass by beneath them.

Somehow the dogs broke through the cornice, and it held stable.

First one dog made it, then another, then another, leaving only Jake to keep the weight of the precariously balanced sled from coming back and crushing Bob. Jake strained. His muscles surged beneath his skin in efforts to obey his demand that they perform beyond their abilities. His claws scratched and tore at the snow for leverage, and the creaking sled rolled its way over the top. It was part of what a good wheel dog does—he pulls the load over as the other dogs relax.

As Bob lay wondering whether he would live or die, crumpled in exhaustion beside the sled on the far side of the ridge, a hundred tons of snow and ice roared by behind him. Sprays of rock, ice, and pine branches fell from the sky. He had made it.

But all was not well. The unbraked sled had rammed into Jake, had trapped the faithful dog beneath it and crushed his hindquarters.

The best damn wheeler on the continent, useless, probably permanently. “Well, guess the wife and I have ourselves a dog,” said Bob. “If that crazy Canadian thinks I’m gonna put a bullet in your head for sav- ing my life, he’s got another thing comin’, sure as shootin’.” Jake was in pain and panted all the harder because of it, in a pitiful sort of way, the way dogs do when they’re vulnerable, in a way that almost seems like they’re smiling.

Bob fashioned a splint and tied Jake to the sled.

Then he sank to his knees. Rest. He needed rest. Five minutes maybe, just enough to allow his heaving heart to slow, just enough to let his terror-stricken mind calm itself. He sat against the sled. His feet slopped themselves out in front of him, and he trembled with a wetness that sank far beneath his skin. His mind began to seek shelter, began to give way to the need for sleep, began to wander to a better place—to thoughts of his honeymoon journey on the Overland Express, when he traveled with Dott to their new life in Missouri, a gift of luxury presented to the bride and groom by the bride’s father…A melting clump of ice negotiated its way inside Bob’s coat to jerk him free from the deadly daydream, to remind him of where he really was. He shivered as it slid down his bare skin. How long had it been? Five minutes? Fifteen? Maybe fifteen minutes too long.

With the strength of Samson he pulled himself to his feet, and in less than a minute he was skimming over the crust, on his way once again to Warfield Hot Springs, the final leg, five dogs in the string now. The dogs were working well, in spite of the trauma, in spite of the loss of their wheel dog. Jake was wrapped in a blanket and tied in next to the bags, his hip all trussed up just like he was a person, and Bob was talking to him like he was a person. “Yes sir, Jake, we’re gonna make it. We’re gonna get up there and deliver us a baby. Nothing to stop us now. No way in hell am I going to go through all this and not have a baby at the end of it.

“Know what, Jake ol’ pal. Me and you, we’re goin’ fishin’ as soon as the snow melts, right when the first crocus breaks through. Fly fishing. Yes sireee.

“Right now though, we’ve some business to attend to. We have a baby to bring into this world, this big ol’ changing world.”

Jake responded with a whine, like he really was listening.

The dogs were still able to travel on top of the light crust. Bob helped when he could by running instead of riding. A time or two he lost his footing and ended up face flat in the snow with the dogs running on out ahead until he could “HO” them to a stop. Once they broke into a run because an animal crossed their path, a fox or a rabbit, jerking the sled forward so hard it nearly pulled his arms from their sockets.

Eventually the light John had promised to set out appeared. Bob had heard the stories of the hallucinations, the snow mirages that plague the long distance drivers up north, and wondered if this was all he was seeing, something made up out of his mind, because his mind wanted it so desperately.

But it was a lantern all right, hanging on the top of a pole stuck in the snow. It was real.

The relief Bob felt must have measured insignificant alongside John Stewart’s when he realized Doc Wright had actually made it. John heard the dogs long before he saw the sled. Dogs have a tendency to begin yelp- ing and sprinting when they sense that a journey is at an end.

The Stewart place was a quarter mile further in, a large one-room house with a barn and a snowed under corral out back. John came run- ning out the door in shirtsleeves and with fear burned into his eyes. “Doc, she’s in an awful way. She’s bleedin’ Doc. She’s bleedin’ somethin’ awful. She’s bleedin’ like somethin’ I ain’t never seen before.”

Bob set the snow hook and strode toward the door, exhausted, emotionally drained—to face the beginning. “How long has she been that way?”

John followed behind him. “Not long. Couple a minutes maybe. The worst of it happened just after we heard your team comin’.”

Bob walked over to the bed without removing his coat, in long, purposeful strides, and sat calmly by Mary’s side, like a father would do to a child, and took off his gloves. “How we doin’ here, Mary? John, bring me my bags in from off the sled.” In times of a crisis, when critical seconds demanded his best, he always remembered what Dr. Durham said those twenty years ago during that high-perched ride in the morning sunshine. “To do your best you’ve got to have a cares-be-damned attitude.” He was right. One has to care without caring.

Mary was rolling her head back and forth on a sweat soaked pillow. The bunched up bed sheets and quilts around her feet were crimson, absorbing the growing flow from her still living body. Mary’s breathing was shallow. She seemed not to feel pain, even as a contraction rolled across her exposed and stretched abdomen.

“Mary, I want you to pay attention to me. Mary. Mary. Keep awake. I’m going to help you now. But I’m going to need your help. I’ll tell you every step of the way what I’m going to be doing. Hear me Mary. Concentrate on what I’m saying.” Bob’s voice came smooth and with self-assurance. It was his way. In the midst of a crisis his fears dissolved. He became a player in a game, an actor in a play.

“John,” he said. “Set those bags down there on the floor. Bring a table over. And an empty pan and boiling water. Quickly now.”

A midwife was there to help, a neighbor. Bob hadn’t seen her at first. She knew what she was doing. She began setting up the table, pouring hot water, laying towels out, taking from his bags pre-sterilized instruments, forceps, scissors, clamps, unwrapping them from their linens and laying them out on the towels.

Bob was sitting on the bed as though he was unaware of the building pool of blood surrounding him, soaking into his clothes. He still hadn’t taken off his coat. There wasn’t the time. Nor was there time to wash and sterilize. He removed the glass stopper from a bottle of carbolic acid and splashed it on his hands and instruments, unconcerned about where it spilled or what it soiled. Its smell instantly permeated the air and gave confidence to those watching. “Mary, what’s happening here, is you’re about ready to have your baby. We have a bit of a problem though. It seems the placenta has slipped down and is blocking the baby’s entrance into the birth canal. What that means is, we’re going to have to get your baby out a little faster. And to do that I’m going to need you to be awake and helping me. All right?” As he was speaking he was forcing his fingers into the membrane of the placenta, ripping it apart and pulling its pieces out so he could secure his hands around the child’s head and guide it into position.

“OK little one,” he whispered. “I’ve got you now. I’ve got you. Here we go.”

When the tip of the head began to clear open air he gripped it with the forceps and pulled. “All right Mary, the next contraction is going to have to bring this child into the world. When you feel it you have to push. Push real hard.”

Mary screamed with the force. A good sign, that she was conscious enough to feel the pressure, and to react to what he was telling her.

One more contraction was needed. “Almost there, one more time.” Again Mary pushed and screamed.

“Aaats my girl. Good girl.”

The child was out—motionless and blue, with the soft sides of its head pushed in from the grip of the forceps.

He clipped the umbilical cord and calmly, swiftly inverted the stillborn and performed the Prochownick maneuver, holding the ankles with one hand, squeezing the diaphragm with the thumb of the other.

The child’s pursed lips fell apart and fluid drained out.

It remained lifeless, free from fear and pain—for the moment.

Soon however, within seconds, its terror would be reawakened and it would be pulled violently into its new and unfamiliar world. A touch from the doctor’s lips would bring the miracle. The Breath of Elisha. Still discounted by most. Fallacious hocus pocus, according to modern medicine. But here, high in the mountains of Idaho—a miracle.

Soon the infant boy’s sensitive skin would be reacting to temperatures thirty degrees colder than that of the womb. Soon his arms would jerk back and he would begin his fall into another existence.

The midwife took the precious baby boy and wrapped it in linens, and held it close to her breast. She herself was a mother; you could tell. Bob was folding pieces of gauze and packing them up into the uterine cavity to press off the blood flow, reaching easily through the still fully dilated cervix, at the same time massaging her stomach so the muscles would loosen, so the saucer sized opening would close. Once the bleeding was stopped and the cervix closed, he could slowly pull the gauze out, strand by strand, and Mary Stewart’s weakened body could begin the incredible process of mending itself.

“She’s all right,” said Bob in reassurance to John Stewart, as the poor disheveled man stared helplessly down at his unconscious wife. “She’s sleeping. She’s weak, but her pulse is strong. She’ll be fine. And your baby, looks like he’s going to be fine too. Don’t be concerned about his head, about the indentation marks. That won’t last.”

The time was a little after midnight. Bob fed and bedded the dogs, then changed into a spare set of clothes he had in one of the bags. He stayed until five, just before the crack of dawn, sleeping a little, checking on Mary, removing the uterine packs, helping her with breast feeding, sleeping some more, checking on the baby, testing its reflexes, sleeping some more.

“Remember—” said Bob as he was readying himself to leave, speaking both to John and to the midwife neighbor. “She needs plenty of fluids. Soup. Lots of soup. Custard pudding is good. If the bleeding starts again, use the sterilized cloth strips that we boiled, and get word to me. She’s got to stay in bed. I’ll be back out next week, in five days, on Thursday.”

The breakfast the midwife fixed him, eggs and potatoes fried up in a big iron skillet, over a stove stoked by sweet smelling cottonwood, was immensely satisfying as it lay in Bob’s stomach, washed down by strong coffee.

John Stewart’s husky voice was spotted a bit with proper Scottish tones and inflections, a rich man’s way of speaking, like he was well educated, though to Bob’s knowledge all John had ever been was a farmer. John was grateful beyond his ability to articulate. Perhaps that’s why he said so little. “Doc. I, I don’t know when I’ll be able to pay—”

Bob put a strong hand on his shoulder. “John. Times will get better. You pay me when you can. I know you’re good for it.”

And times did get better. And the Stewarts did pay, two years later when Mary had her next baby. Then they paid for that one when the next one came, and so on.

The storm had passed, and the air was cold and the sky blue. The Chinook had left the snow cover crisp and hard, glistening before the mountain sunrise, like it was water, smooth and white. Bob had to reach down and touch it, run his hand across it, to make sure it was real. The tops of the mountains, above yesterday’s temperature inversion, were dusted in sugar. They touched the powdery sky with majestic serenity, touched the remnants of empty clouds drifting slowly upward to blend into the blueness. The sides of the mountains were torn by the jagged pathways of the snowslides that had lacerated them to bare rock and dirt. The largest of the slides had buried the creek and created an arctic lake from the backed up water. It must have been the one that nearly cost him his life, three lives, nine lives including the dogs.

The down hill journey was smooth and fast. He rode the runners and seldom had to push, and closed his eyes when he could to protect against snow blindness. And the peace of his accomplished task rode with him, transforming each moment into something incredible. Thoughts of his honeymoon came again to mind, the burnished black and bronze engine, nearly twenty feet tall at her stacks and four times as long, and her lengthy line of palace Pullmans stretching a mile to the rear, sleek and dark and green. He was remembering the way she sat idling on one of the dozen or so tracks and sidetracks and switch-lines at the Ogden station, obediently containing her power. “Serene, she was, Jake my boy.” Jake lifted one of his floppy ears. Who knows how much is understood by a loyal dog. Bob was convinced Jake understood it all. “Engine 1849, stamped right there on her nose. Steam rolling out from underneath her wheel beds. Flexing those mighty muscles. Quite a sight, Jake my boy, quite a sight.

“I was a mighty proud man, walking along that platform with that pretty wife of mine in her Queen Mary dress. I remember she had this large-brimmed flowered hat that was kind of tilted to one side. How’d I ever get so lucky, to get a woman like that? It’s not just that she’s pretty, but smart too, and damn loyal. Damn loyal. A lot like you.

“That trip on the Overland, I sure do remember that, sure do. Before we boarded her we bought these fresh baked rolls from a bakery nearby. You could have smelled ’em all the way to Timbuktu. Just out of the oven. So warm the butter and the frosting was dripping off the sides onto your fingers. Ummhh. Like heaven.

“The Wellington. That was the name of our car. The Wellington, Vestibule Sleeping Car. They couldn’t just say sleeping car. It had to be vestibule sleeping car. It was written in solid gold on the side. And inside—it was the damnedest thing you’d ever seen—dark green leather upholstery, gold transoms, gold scrollwork, a bath for Dott on the left, one for me on the right, with hot and cold running water.

“I was awake when we eased into Cheyenne. It was nigh on about midnight. I was watching Dott. I do that sometimes. Just watch her sleep. There was a full moon out. It was small, hanging inside this hazy ring of ice-cold softness. The reason I remember it, it was shining its light right through the window onto Dott’s long hair. Red hair. Light red, almost blond. It turned it kind of silvery. Lord almighty I love that hair of hers. You’ll be meeting her pretty soon. You’ll like her.

“Next morning, sooner than we would ’a liked, we saw the Missouri River Bridge. The end of the journey. Now that’s a sight to see. It’s this huge iron span connecting Omaha and Council Bluffs, double-tracked. And way up high, way up at its highest point, is this massive copper buffalo head. The unofficial gateway to the west, they call it. Some say it’s a guardian, for the people that pass beneath it on their journey into the new land, casting down good fortune.”

“Surprise for you,” he said to Dott when he walked in the front door carrying Ol’ Jake, cradling him like a baby, Bob’s unbuttoned and blood- stained horsehide coat falling on both sides of the animal. “It appears a retired sled dog’s coming to live with us.”

Dott had a couple of surprises of her own, dinner kept warm and moist for twelve hours, and an announcement that sometime in July or August, she was pretty sure, she also was going to have a baby. “Hopefully you’ll be able to find the time to deliver it,” she said, the side corner of her mouth lifting slightly to show it was said lovingly, but nonetheless with absolute seriousness.