One of the most exciting aspects of publishing history books is discovering unexpected connections. Not long ago, we had one right in our office. Our staff members were assigning covers and discussing our new season’s titles when one of our designers offered a surprising revelation. Our list included a book about the Minidoka War Relocation Center called, An Eye for Injustice. Some time ago, members of his family had purchased a lot from a Spokane estate sale, and inside one box he came across a set of old letters that detailed facets of a poignant story—one very similar to experiences the book portrayed.

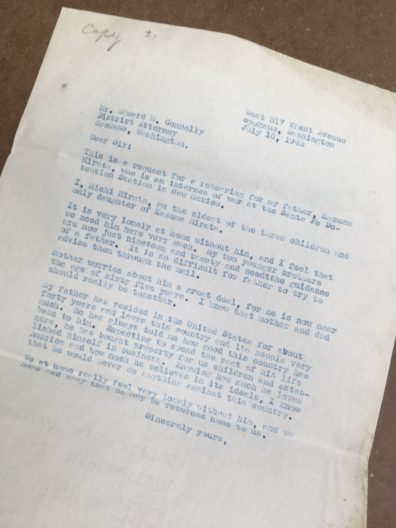

He brought them to work, and it was heartbreaking to hold World War II era letters that revealed a family’s suffering. Especially touching were Michi and Shingo Hirata’s inquiries about securing their father’s release—Michi shared how lonely it was without him, and Shingo offered to take his place—from the Santa Fe Internment Camp in New Mexico. That location was under the Department of Justice, and smaller than Minidoka. The packet included letters (some as drafts) to and from Edward J. Ennis, Director of the Department of Justice’s formidably named Alien Enemy Control Unit, and one from United States Attorney Edward M. Connelly, granting a rehearing. Envelopes display censorship tape, and there is additional untranslated correspondence in Japanese. We also found handwritten drafts documenting Tsunejiro Kurita’s efforts to establish that he was in the United States legally—all sobering reminders of what Japanese Americans lived through during the war. For us, it brought new meaning to our book, which we just released this week.

The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on the morning of December 7, 1941, and the FBI arrested Kazuma Hirata, known as Frank, that evening. With his wife, Jun, he owned Spokane’s Clem Hotel. He also was president of the Japanese Association’s local chapter. United States officials never brought formal criminal charges or linked him to espionage, yet he spent more than two years in federal prisons. He was released in February 1944. Searching online, we found photos and more about his life in this Gonzaga Foley Library post.

Our designer hopes to find an appropriate home for these historical documents. Perhaps they can join the Hirata Family Papers held by the Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture/ Eastern Washington State Historical Society.